Circular Economy in Community Arts

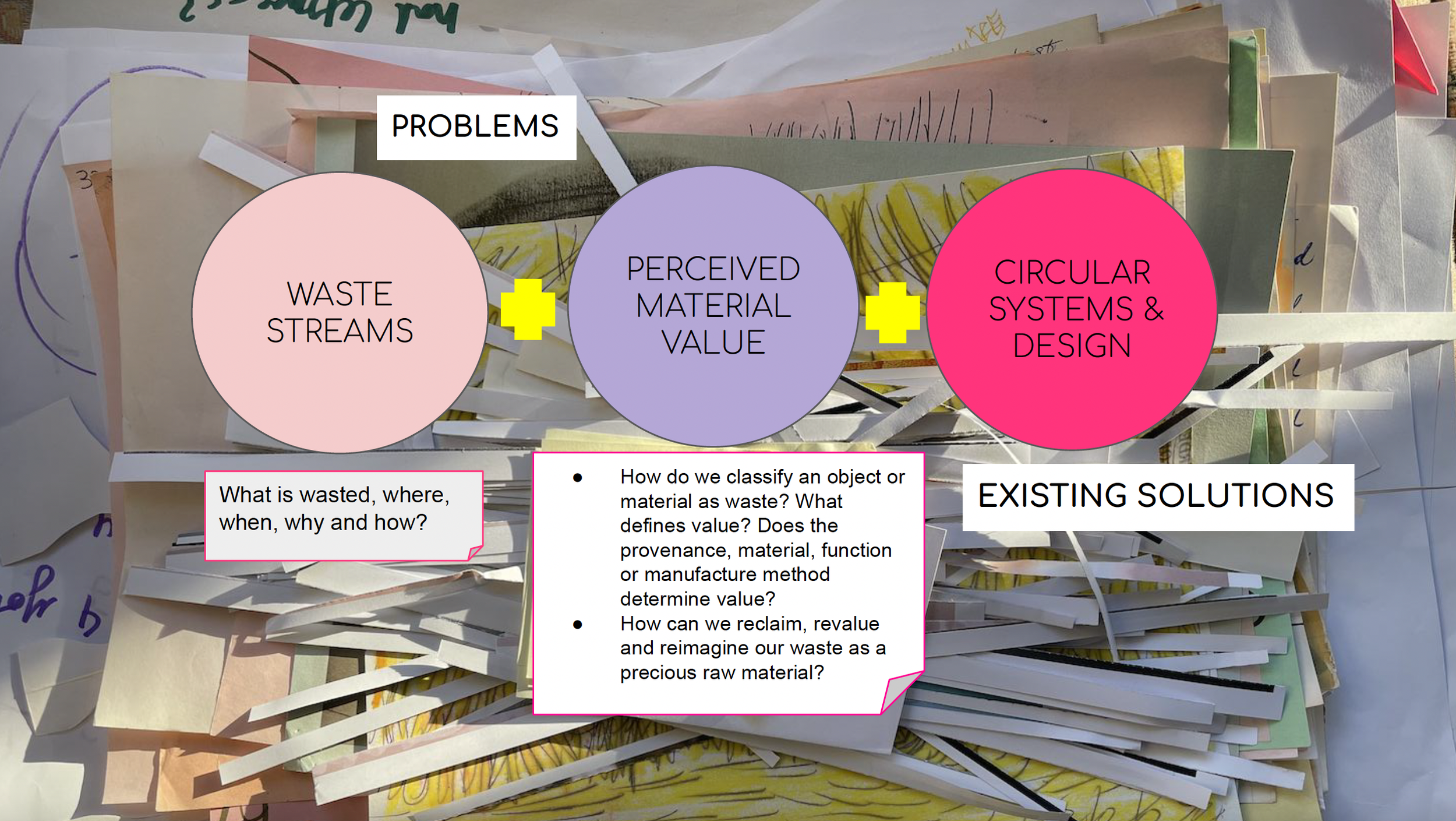

How can we encourage collaborative and creative social impact through reuse of waste materials within existing circular networks at community level as to Reclaim, Reimagine and Renew?

‘Waste’ materials can pose both an eco-social problem and opportunity. In today’s Anthropocene era, capitalism feeds consumerism that necessitates consumption. From the convenient paper and plastic coffee cup so easily disposed of, to the factory floor offcuts of fabric leftover from the production of fast fashion T-Shirts, to the skins of the vegetables peeled and discarded in our kitchens at home, one thing is clear - waste is inevitable.

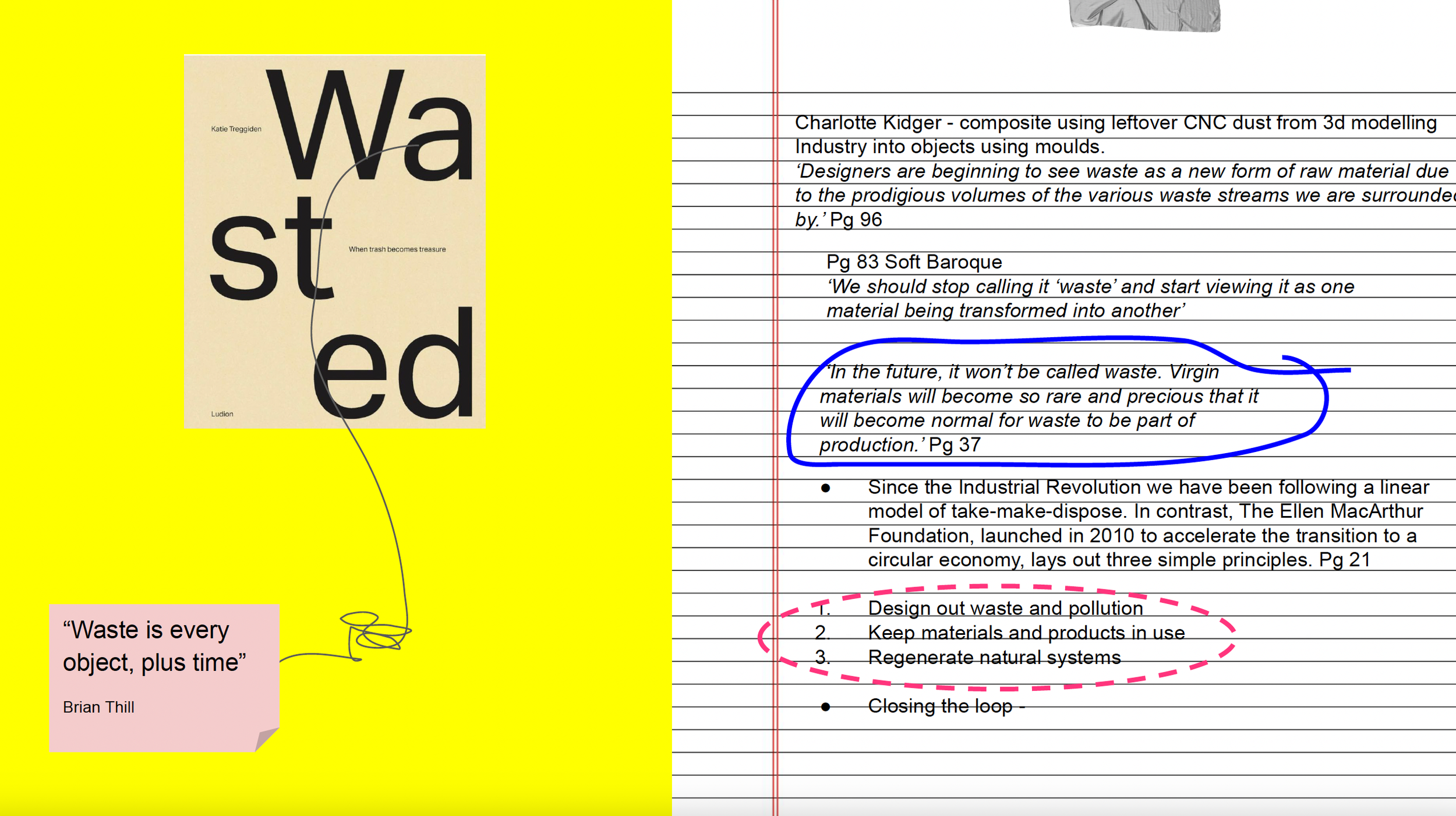

‘Though we try to imagine otherwise, waste is very object, plus time.’ (B.Thill, Waste, 2015)

Once we consume something and its original purpose has been fulfilled, it is no longer perceived to be of value and destined ultimately for landfill or incineration. This is perpetuated by industry systems such as planned obsolescence, where products are manufactured at low quality for a short life span, therefore promoting the take–make–waste model of our current linear economy. (K.Treggiden, 2020) However, we need to question what opportunities and endless potential could be tapped into if we recategorised ‘waste’ as a valuable resource.

Keeping materials in use means reimagining waste and by-products as raw materials for other systems - either manufacturing or ecological (K. Treggiden, 2020)

Alongside redefinition of our existing negative perceptions of waste, what resources and support systems would be required to encourage use of discarded and surplus materials through craft, creativity and design? As a revision of the traditional 3 R’s Reduce, Reuse and Recycle, how can we encourage collaborative and creative social impact through reuse of waste materials within existing circular networks at community level as to Reclaim, Reimagine and Renew? In order to understand the reuse ecosystems of pre and post consumer waste streams, this report will firstly critically examine the environmental and social impact of waste before analysing existing models of circular organisations, recycling centres and scrapstores at a community level in and around London.

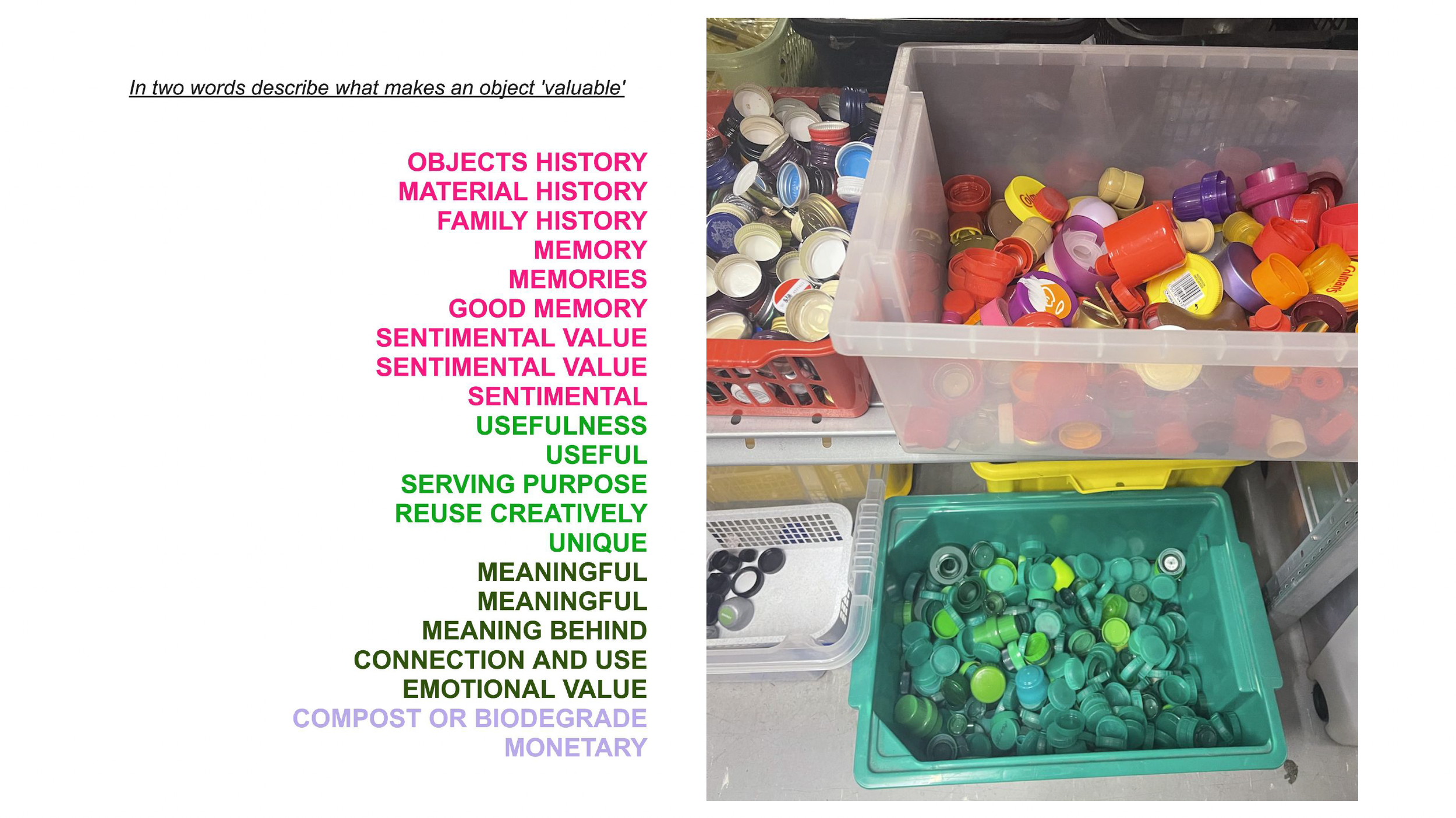

The results of a survey exploring personal value systems and how people classify materials as waste.

THE WASTE PROBLEM - ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

The environmental need to reduce waste requires simultaneous reduction of production and consumption in order to limit the extraction of natural resources and resulting pollution. The world’s population is rapidly approaching 8 billion, with each person on the planet generating an average of 0.74 kilograms of waste a day and up to 4.54 kilograms within high-income countries, a total of 2.01 billion tonnes of global waste is generated annually (World Economic Forum, 2022) This clearly demonstrates the macro and micro issue which will require both individual and collective widespread action for change. Furthermore, whilst Methane is responsible for around 30% of the rise in global temperatures since the industrial revolution, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the waste sector is responsible for 20% of global methane emissions and 3.3% of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to a new report, 'Zero Waste to Zero Emissions: How Reducing Waste is a Climate Game-changer' from the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA)

With planet earth's valuable resources being diminished, degraded and destroyed we need an epistemic change in the way we perceive value in the things we consume once they no longer fulfil their primary purpose in order to reduce and utilise waste. According to The Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP, 2015) a global climate action NGO, the ecological and social benefits of preventing waste include the following:

● Minimises greenhouse gas CO2 emissions

● Encourages social inclusion and economic development - through creation of jobs, volunteer schemes and training opportunities and improving access to reduced price goods for lower income families.

● Saves consumers money - consuming less will use fewer financial resources to purchase products that become waste.

● Reduces demands on finite natural resources

Aerial view of used clothes discarded in the Atacama desert, in Alto Hospicio, Iquique, Chile, on September 26, 2021. MARTIN BERNETTI / AFP / Getty Images

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation was launched to accelerate the transition to a circular economy that decouples economic activity from the consumption of finite resources, laying out three simple principles:

1. Design out waste and pollution

2. Keep materials and products in use

3. Regenerate natural systems

Based on these principles the ultimate solution is to prevent waste from ever occurring within the design stage, However, in order to achieve the goals of a fully circular economy, a global change of current systems and societal behaviours and values is required. Though sustainable practices in recycling and up-cycling are solutions at the end of the life cycle and do not provide a solution to the wider scale problem, they are part of the solution and can promote changes in lifestyles. Poor waste management contributes to climate change and air pollution, and directly affects many ecosystems and species. Landfills, considered the last resort in the waste hierarchy, release methane, a very powerful greenhouse gas linked to climate change. (European Environment Agency, 2014)

Whilst researching into the disposability of the culture we live in and the value we place on the objects we consume, a point raised in a Discard studies article in “ranking some things as valuable often devalues other things.” as Max Liboiron states. With this in mind, I reflected on the IDOART process and conducted a participatory workshop with the aim to explore how people classify and value materials and the potential impact of craft and storytelling on building a connection to revalue waste materials.

“Classifying, defining, sorting, ranking things by value, and other forms of differentiation–creating and acting on difference and similarity–are central to discarding.These activities are not good or bad in themselves, but nor are they merely technical: defining things by one set of characteristics means other characteristics are not accounted for and become unimportant in the definition system; ranking some things as valuable often devalues other things.” (M.Liboiron, Discard Studies, 2020)

Stills from videography of participatory session assessing participants perceived value classification of various materials.

Trash to Treasure workshop, UAL, 2023

CREATIVE REUSE + SOCIAL IMPACT;

CRAFT, COMMUNITY AND UP-CYCLING

Crafting and up-cycling are an accessible and tangible way for people to learn to consciously consume and reuse what they already have. Sustainable organisations and initiatives reusing materials at grass root community level can be an important driving influence in demonstrating these alternatives to disposal and promote the benefits of living a more sustainable lifestyle. This concept opens the question: How can we implement de-growth solutions that interlink environmental and social justice?

“By reminding ourselves that we are part of an ecosystem-valuable members of an intricately beautiful, life-affirming community-we can begin to heal the wounds caused by profit-seeking, productivity and extractivism.” (G.Johnson, The Slow Grind, 2021)

One method of reusing materials is through a process of ‘up-cycling’ where discarded clothing, objects or materials are remade into a product of higher quality or value that the original. Product lifetimes can be significantly extended through making more use of them or passing them on to others. Remanufacturing, repairing and re-use are all ways we could ease demand for materials (K.James, WRAP, 2015) By revaluing and transforming materials into something new, not only lengthens the lifespan of materials, it offers opportunity for entrepreneurship, employment, financial gain, learning and up-skill.

Examples of design intervention in the reuse and up-cycling of materials include handcrafts such as weaving, quilting and natural dyeing. A transition from consuming disposable fast fashion cheaply made for short life span based on ever changing trends to appreciating the craftsmanship, care and human care behind the products produced from slow production methods can be a way to foster revalue of ‘waste’.

Making is a powerful tool - it builds communities, boosts wellbeing and can empower people to refashion their lives. Working with materials can help people in difficult circumstances grow in confidence and rediscover a sense of agency (Craft Council, 2023)

The beauty of craft, community and connection communicated through storytelling of reuse of waste materials can tap into the needs and wants of consumers by connecting with people's emotions.

‘Weaving in the Woods’ - New York Textile Month 2023 event facilitated with Intertwine Arts

Scrapstores, usually charity or community organisations led by volunteers, divert surplus and ‘waste’ materials from local industry and commercial businesses otherwise destined for landfill that are donated for reuse in local communities. Redistribution into the hands of children, young people and adults offers endless opportunities for creative play, education and enterprise. Scrapstores provide the environmental benefit of reducing carbon emissions produced in the waste management process of incineration or landfill whilst reducing the requirement for virgin and synthetic, man-made materials that drain valuable natural resources and generate toxic pollution. One example of the ecological benefits is that of the Work and Play scrapstore, who have been cutting carbon emissions through reuse of over 60 tonnes of waste each year. (Work and Play scrapstore, 2023) They are the perfect link between businesses and consumers and work in a very simple and effective way. Clean industrial scrap material, such as textiles, paper, foam, plastics, carpet, leather, ribbons, paint and any other craft material is collected by the scrapstore. (The Watford Recycling Arts Project, 2010)

Aside from the ecological benefits of reusing waste, the social accessibility to valuable resources helps inspire and promote creativity in the arts, within groups including those marginalised from mainstream society including disabled, migrant and low income groups who may otherwise have less access to funding and resources. The MKPA Scrapstore is an initiative of the Milton Keynes Play Association charity who believe that by learning through play all children can learn essential skills that will help them throughout their entire life (MPKA Scrapstore, 2023) Mapping their current stakeholders, scrapstores are well connected with community groups in particular childrens education and have well established networks including local schools, nurseries, care support and charities. Any strategy for change would therefore need to enhance the existing replationships as well as building new ones.

From research conducted across the three scrapstores it can be seen that there is a gap within the creative and design services and resources offered to support creativity, innovation and enterprise. There is a lot of opportunity for these centres to more closely collaborate with designers and students with the huge potential presented by the variety of quality materials available. Initiating creativity and design by linking the skills of designers and crafts with community groups accessing the scrapstores can accelerate social impact.

Social innovation occurs when people, expertise and material assets come into contact in a new way that is able to create new meaning and unprecedented opportunities. (E. Manzini, 2015)

A further issue as shown in the map below, shows localised accessibility to use of a scrapstore is not widespread with only around 100 sites across the UK, further supporting the need for a connecting service and interlinking between other circular material reuse organisations for maximum social impact where it is needed.

Community is at the heart of social change, in dialogue with local people, educators will coordinate communities of learners, building theory in action that is capable of informed action for change. An altered way of seeing the world emerges from an awareness that creates an epistemological shift, a new way of making sense of the world that seeks the root causes of inequalities. Rather than passive objects, the ‘others’ of a society based on status and privilege, this process locates people as thinking, active subjects capable of transforming the world as stated by (P .Friere, 1988)

REFERENCES:

B.Thill (2015) Waste, Bloomsbury Publishing

K. Treggidein (2021) In conversation with Katie Treggiden, on craft, design, and the circular economy. Available at: https://leap.eco/in-conversation-with-katie-treggiden-on-craft-design-and-the-circular-economy/

K. Treggidein, (2020) Wasted - When trash becomes treasure, Pg21, Ludion

A. Matthey (2010) Less is more: the influence of aspirations and priming on well-being Journal of Cleaner Production, pp. 567-570 Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016328715300355

European Environmental Agency (2014) Well-being and the environment. Waste: a problem or a resource? Available at: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/signals-2014/articles/waste-a-problem-or-a-resource#:~:text=Air%20pollution%2C%20climate%20change%2C%20soil,gas%20linked%20to%20climate%20change

The Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) (2015) Household Waste Prevention Hub: The environmental, social and economic benefits of waste prevention, available at: https://wrap.org.uk/resources/guide/household-waste-prevention-hub/environmental-social-and-economic-benefits-waste-prevention

S. Ellerbeck, World Economic Forum (2022) COP This is how cities can reduce emissions with waste-reduction solutions, available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/11/waste-emissions-methane-cities/

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2023) The Circular Economy and Reuse, Available at: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/podcasts/ep-101-the-circular-economy-and-reuse

G. Zilli (2010) The Ecologist, The Watford Recyling Arts Project (WRAP)

Scrapstores: turning waste into arts and crafts, available at: https://theecologist.org/2010/feb/09/scrapstores-turning-waste-arts-and-crafts

K.James, The Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) (2022) WRAP’s blueprint for reaching net zero through transforming consumption habits, available at: https://wrap.org.uk/blog/2022/09/g7-x-7-wraps-blueprint-reaching-net-zero-through-transforming-consumption-habits

G.Johnson (2021) The Slow Grind - Finding our way back to creative balance, Independently Published by Curator Georgina Johnson

M.Ledwith (1988) Community Development in Action - Putting Freire into Practice, Policy Press.

E. Manzini (2015) Design, when everyone designs. An introduction to design for social innovation, pg 77, The MIT Press

Work and Play Scrapstore (2023) Available at: https://www.workandplayscrapstore.org.uk/

Milton Keynes Play Association (MKPA) (2023) Available at: https://www.mkpa.co.uk/

C.Earney UNHCR Innovation - What is an innovation lab? (2015) Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/innovation/what-is-an-innovation-lab/

Craft Council (2023) Learning - Participation, available at https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/learning/participation